Fears over the spread of the coronavirus are making headline news. With an epicenter in Wuhan, China, cases have been reported around the globe. While official estimates put the infection rate in China at nearly 3,000, a whistleblower has come forward to say the number is closer to 90,000. In a frantic bid to stem the flow of the virus, Chinese officials have canceled Lunar New Year celebrations, quarantined over 35 million people, and ordered the construction of two 1,000-bed hospitals in just six days. As health officials around the globe race to understand and contain the disease, it is a worthwhile exercise to look at events from a sociological perspective.

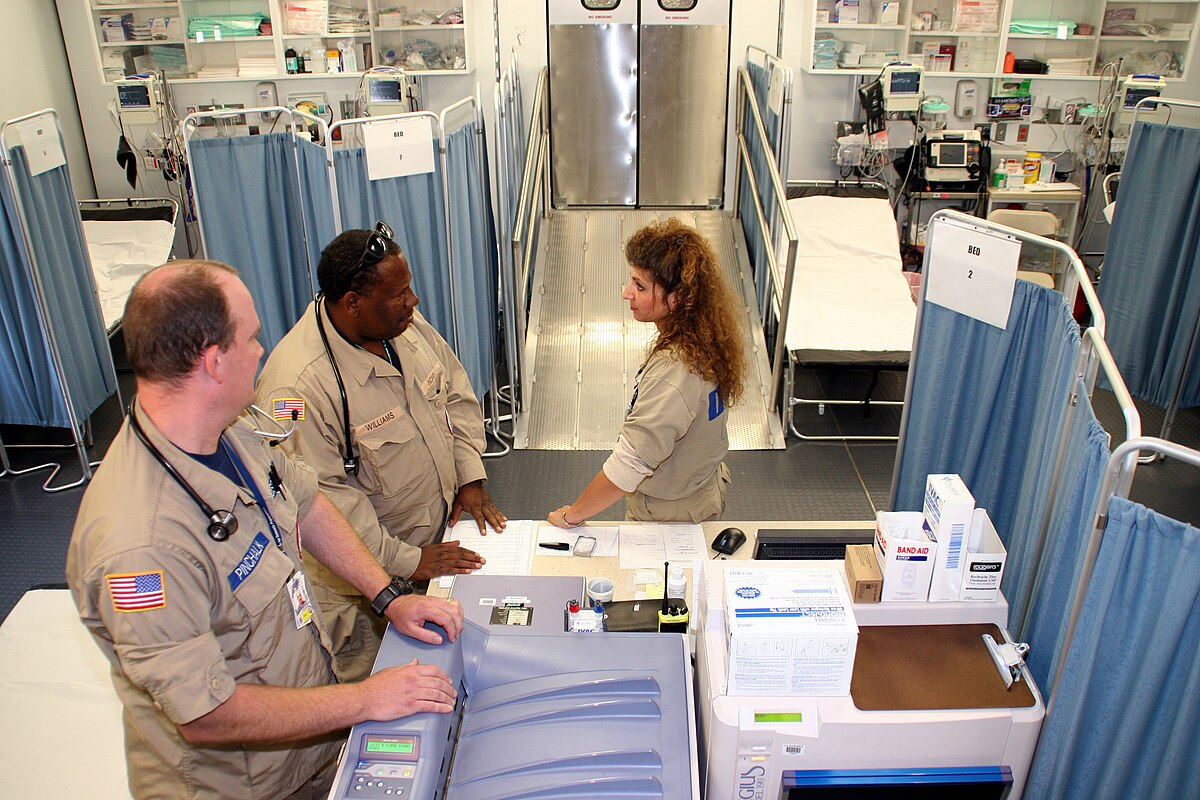

Functionalist theory, a macro view of how the parts of society serve to maintain stability, gives us an opportunity to consider how the different parts of society are working together to address this illness. From the TSA (Transportation Security Administration) workers screening passengers on flights from China to CDC (Center for Disease Control) officials monitoring suspected cases on the ground, different segments of societies in the U.S. and abroad are working tirelessly in a bid to maintain stability and social order.

Because it is a new disease, groups have not yet developed herd immunity, the population’s ability to resist a disease because of a high percentage of its members being immune, making its impact potentially devastating. Governments in France, South Korea, the U.K., and the U.S. have decided to evacuate their citizens from Wuhan via chartered planes. This is being done out of an abundance of concern for their health, a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. While the news media may report this disease from a macro perspective, a level of analysis focusing on social systems and populations on a large scale, it is important to remember that people often experience their fears about this disease from a micro perspective, a level of analysis focusing on individuals and small groups within the larger social system. Our deepest concerns associated with coronavirus are not about secondary groups, large-scale, impersonal, task-focused, and time-limited associations, like corporations, factories, and political parties. Our deepest concerns are about how this disease might affect our primary groups, small-scale, intimate face-to-face, long-lasting associations, which include our families and friends.

As sociologists, we are encouraged to have verstehen (vûrst-e-hen), an empathetic approach to understanding human behavior, even as it relates to the impact of this virus. In doing so, we must remember that experience (including that of disease) is not one-dimensional. Everyone experiences the effects of disease and illness differently due to individual factors and varying backgrounds. Usually, these factors are not isolated. They are compounded as we experience an intersection of race, sex, gender, religion, and social class — to name a few. In sociology, this is referred to as intersectionality and is defined as the overlap of personal and social identities that manifests as disadvantage and discrimination in people’s lives.

Thompson is a co-owner of UITAC Publishing. UITAC’s mission is to provide high-quality, affordable, and socially responsible online course materials.

Images used in this blog:

- “People Holding White Paper With Pandemic Covid19 Text” by cottonbro studio is licensed on Pexels. This image has not been altered.

- “Woman Looking at a Microscope” by Edward Jenner is licensed on Pexels. This image has not been altered.