Over the course of your lifetime, how many people have you met with the same name as you? Twenty? Fifty? Five hundred? In the United States, names like James and Mary are very common. On the other hand, in Egypt, Ahmed and Sara are also common names. The most common last names around the world are Wang, Hernández, Mohamed, and Smith. Our names are a representation of us, our family, and our larger community. But what happens if you lose your name? Not simply change it, as many choose to do when they get married, but lose all rights to it? Currently, many citizens of North Korea are experiencing that reality. North Korea’s hereditary dictator, Kim Jong-un, has ordered that anyone with the name Ju-ae has one week to find a new name. Why? Because that is his nine-year-old daughter’s name, it has been decided that she will be the only person in the country with that name. It doesn’t matter if you have lived with that name for five weeks or fifty years; it is now considered a name with the “highest dignity” and is, thus, reserved for members of the North Korean ruling family. This is not the first time this has happened in North Korea. The names of the aforementioned leader and his wife, Sol-ju, are also off-limits.

From a sociological perspective, the name issue in North Korea is fundamentally about social status, an individual’s position or rank within a social system. Those with the right status (e.g., members of the ruling family) have the freedom to decide their names. To a certain degree, they also can determine the names of others by making certain names off-limits. Not all members of the North Korean elite have this authority. Being a North Korean general with achieved status or earned social status based upon merit doesn’t give you the power to outlaw specific names nationwide. That power is within the hands of a select group of people with ascribed status. While, typically, ascribed status is thought of as assigned social status based on characteristics such as sex, race, and age, other factors such as one’s social position at birth also qualify. For example, like Kim Jong-un, King Charles of Great Britain has ascribed status based on his sex, race, age, and position of birth in the British monarchy.

The question we are left pondering is how the North Korean people feel about these enforced name changes. If you were to visit the country, it might be hard to find anyone displaying anything other than a positive reaction. In fact, feeling rules, norms about which emotions are appropriate to display in a given situation, are very evident in North Korean society, particularly when mourning the death of a leader. But would these public responses be the whole story? No, not if one considers dramaturgy, the theory that we are all actors on the stage of life, and as such, we divide our world based on what we let others see and don’t see of us. According to this theory, people divide their world into front stage, a person’s public life that they reveal to the world, and backstage, a person’s private world that they choose not to reveal. While you might not know someone’s true feelings about losing their name, members of their family or primary group, made up of small-scale, intimate, face-to-face, long-lasting associations, may have access to more honest insights.

Understanding the impact of losing one’s name in this manner requires a definition of the situation, an individual’s interpretation of the social setting, that is beyond the scope of most outsiders. Ethnomethodology, the study of people’s methods as it relates to the formation of society, would be a wonderful way to investigate the questions posed above. Doing this type of research would also increase our understanding of the North Korean social construction of reality, an individual’s perception of one’s social world is determined or influenced by social interaction. Maybe by better understanding the North Korean construction of reality, we would be able to better understand our own.

Thompson is a co-owner of UITAC Publishing. UITAC’s mission is to provide high-quality, affordable, and socially responsible online course materials.

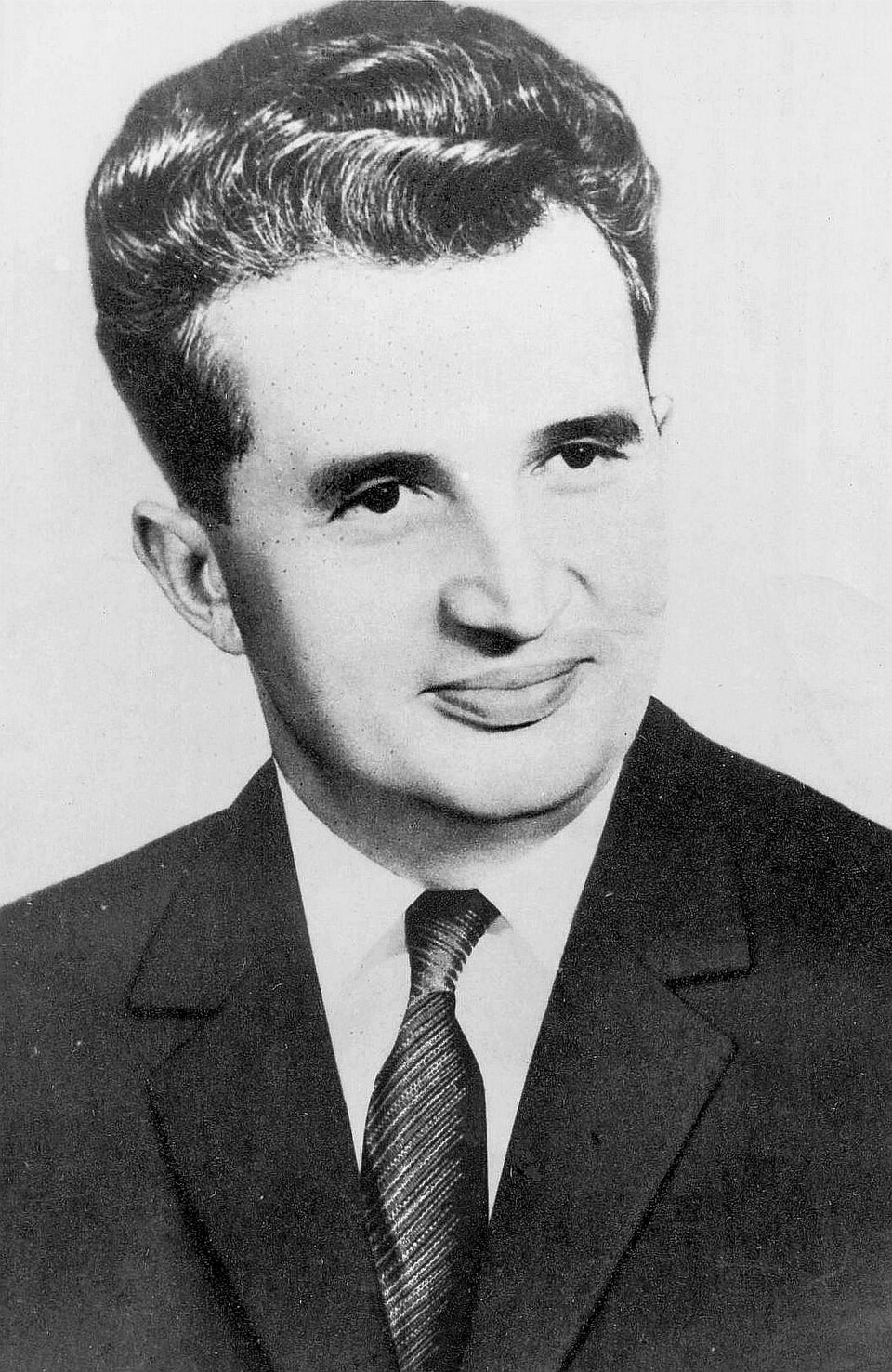

Images used in this blog:

- “Kim Jong Un with Honor Guard portrait” by Cheongwadae / Blue House is licensed under the Korea Open Government License Type I: Attribution. This image has not been altered.

- “Beckenbauer Pressefotografen2” by DerFalkVonFreyburg is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. This image has not been altered.

- Photo by Kevin Schmid is licensed on Unsplash. This image has not been altered.