As the semester draws to a close, attention turns to upcoming celebrations. For some, this includes Hanukkah, Christmas, and Yule. For others, their focus is on Kwanzaa, Boxing Day, and Omisoka. Regardless of which festivity you partake in, it is a worthwhile exercise to use the sociological framework to better understand how these celebrations fit into our personal lives and how they impact the larger world.

As we learned earlier in the semester, culture is the socially learned and shared ideas, behaviors, and material components of a society. You cannot have a society without culture, and you cannot have culture without a society to maintain it. Aspects of culture are foundational to the celebrations in society. Many of these combine both nonmaterial culture or ideas and symbols that represent components of society and material culture, the physical artifacts that represent components of society. Hanukkah, an eight-day celebration, commemorates the Maccabean victory in 139 BCE. Its celebration includes blessings and lighting candles, but also a variety of foods and presents. Kwanzaa is a seven-day African American cultural celebration that was started in 1966 by Dr. Maulana Karenga at California State University. It emphasizes nonmaterial ideals and symbols but also includes a material culture gift exchange on the last day.

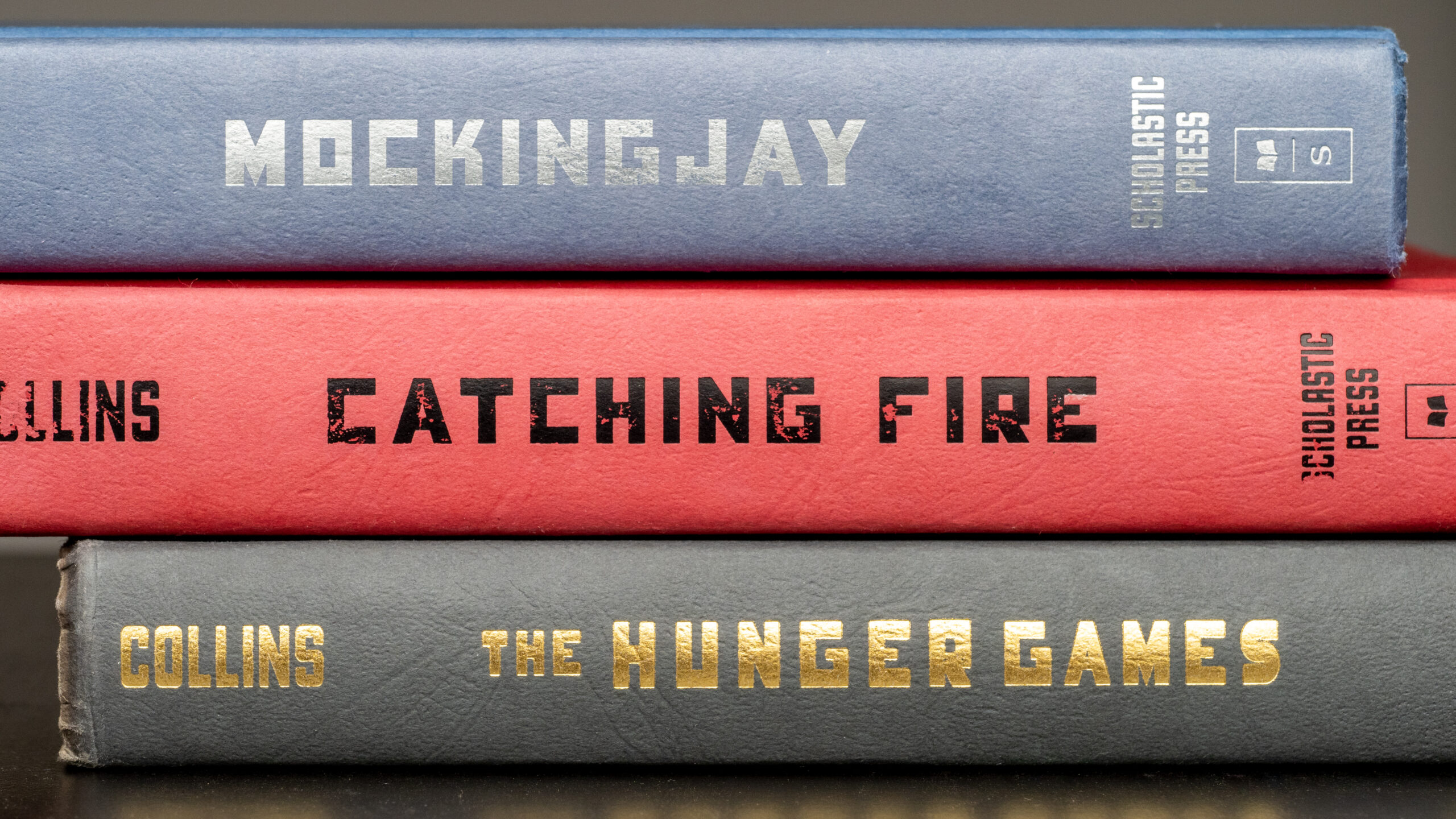

Some form of Christmas observance takes place in 160 countries around the world. While many in Western societies celebrate on December 25, in Ethiopian culture, they follow the Julian calendar, so their actual Christmas observance is on January 7. Regardless of location, some celebrants treat Christmas as sacred, believing observance requires special religious treatment. Others approach the day not necessarily from the profane or ordinary and familiar realm of everyday existence but with an emphasis on purchased goods as opposed to religious reflection. Technology, tools created by science to address and solve the problems of mankind, is a particularly favorite gift. Businesses spend millions targeting advertisements to digital natives, those individuals who have always experienced a totally digital world.

Whether referring to cellphones, baby dolls, or clothes, the sad reality is that many of the goods exchanged at holiday celebrations are manufactured in sweatshops, factories that offer their workers low wages and long hours in dangerous working conditions. Globally, millions of people are forced to work in sweatshops, while most consumers are blissfully unaware. Arguably, this disconnect occurs because, on our celebration days, we prefer to lean into the narrative of the ideal culture — the ideals and values that a society professes to believe — while turning away from the truth of real culture, the actual behavior of members of society. It is hard to celebrate a gift knowing that sweatshop workers who made it earned as little as 3 cents an hour. This is particularly true in a society where the average factory worker earns $16 an hour and wouldn’t even consider working for pennies.

Would knowing about the conditions of sweatshop workers influence the behavior of holiday celebrants? Ideally, but upward of 48 percent of Americans say they prefer not to know about the manufacturing processes behind the goods they purchase. Concerned advocates contend that purchasing Fair Trade goods is the solution to this issue. Fair Trade is an organizational movement and certification process to help producers in developing countries receive a fair price for their products with the goals of reducing poverty, providing for the ethical treatment of workers and farmers, and promoting environmentally sustainable practices. Of course, paying sweatshop workers a fair price for their time and labor will increase the price of the goods, putting many products beyond the financial reach of consumers.

What does it say if we choose not to know the truth about how our products are made and how the workers are treated? Sadly, such a laissez-faire attitude means that consumers are choosing to honor the ideals of their celebration over the lives of the workers, thus contradicting the very nature of the celebration itself.

Thompson is a co-owner of UITAC Publishing. UITAC’s mission is to provide high-quality, affordable, and socially responsible online course materials.

Images used in this blog:

- “Close-up of Christmas Decorations” by Tofros is licensed on Pexels. This image has not been altered.

- “Whisky, Modern face of whisky, Whisky drinker image” by OurWhiskyFoundation is licensed by Pixabay. This image has not been altered.

- “Garment Factory Worker Bengaldesh” by Solidarity Center is licensed under CC BY 2.0. This image has not been altered.