Note: This blog is intended to provide a sociology perspective of issues that arise during humanitarian crises due to race/ethnicity-based conflict.

Trigger Warning: This blog discusses sensitive and potentially distressing topics, including unethical, non-consensual, and inhumane health treatment. Reader discretion is advised.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Race and ethnicity are categories that profoundly shape people’s lives and experiences. Race is a socially constructed category of people based on real or perceived physical differences, while ethnicity refers to social and cultural characteristics that separate one group of people from another. In the realm of sociology, they are crucial lenses through which we understand human experiences, especially in contexts of conflict. Both play a significant role in how individuals are treated, how resources are allocated, how they experience conflict and displacement, and health disparities.

When groups with different racial or ethnic identities come into conflict, it can lead to discrimination, unfair or differential treatment of individuals and groups based on race and ethnicity. This discrimination can range from personal biases to larger systemic issues like unfair laws or practices. As conflicts worsen, this discrimination can evolve into what is known as institutional racism.

Medical Apartheid and Genocide

When a majority group, a group that controls the economic, social, and political power and resources, utilizes institutional discrimination, the use of social institutions to deny minority group members access to the benefits of society, and institutional racism, societal patterns that produce negative treatment against groups of people based on their race, it can lead to an apartheid, policies, regulations, and laws implemented by a government to keep radical and ethnic groups separate. While apartheids themselves cause health disparities to develop by affecting overall well-being and mental health of minority groups, it can take form by targeting specific aspects of life, like economic, education, and health outcomes. The latter case can specifically be referred to as ‘medical apartheid.’

Although ‘medical apartheid’ has no formal international human rights law definition, it is commonly referred to as segregation and discrimination in health care. Yet, this type of treatment can escalate to loss of bodily autonomy and result in systemic harm. These practices perpetuate inequality by denying certain groups access to quality care, subjecting them to unethical medical experimentation or withholding vital treatments — ultimately violating the fundamental human right to health. Once a conflict worsens beyond this level with intention, it can be considered a genocide, the systematic killing of one group based on differences in race, ethnicity, and religion. Historically, this has occurred in numerous contexts, such as:

- during the South African Apartheid, substantial health disparities formed among Black populations due to segregation of health institutions and treatment quality;

- during the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act of 1970, Indigenous women in the U.S. were subjected to forced sterilizations;

- during the Aversion Project, homosexual men were subjected to shock therapy and non-consensual gender reassignment surgeries in the South African Defence Force;

- during World War II, Nazi medical experiments on were carried out against Jewish individuals in concentration camps;

- during the Rwandan Genocide, attacks on health infrastructure and humanitarian aid hindered the delivery of essential healthcare to the Tutsi minority.

These historical actions highlight how ‘medical apartheid’ and genocide serve as tools for maintaining social hierarchies, reinforcing existing power structures, and marginalizing vulnerable communities. The systematic denial of health care to specific groups not only perpetuates social inequality but also normalizes the dehumanization of these populations. As a result, they also erode social cohesion, foster distrust in institutions, and exacerbate divisions along racial, ethnic, and economic lines. These sociological implications deepen and perpetuate cycles of exclusion, making it difficult for affected communities to access justice and equal opportunities for well-being.

Current Conflicts and Health Impacts

However, this type of conflict and its discrimination that exacerbates health issues do not only lie in history but continue to occur today. Most notably, this includes the ongoing conflict and humanitarian crisis in Palestine, which has been characterized by long-standing conflict and violence, particularly in Gaza and the West Bank due to direct population transfer, when the dominant group makes a minority population leave a location by force. While the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has ruled that a genocide is plausible in Gaza and ordered Israel to ensure its forces do not commit any acts prohibited by the Genocide Convention, the term “genocide” continues to be debated among the public and scholars. Despite this, there is broad recognition of the humanitarian crisis and severe health implications facing Palestinian civilians with 50 percent of Americans saying they favor providing humanitarian aid. These impacts include effects on health services, infrastructure, and the psychological well-being of the population:

- Access to Healthcare. The conflicts in Palestine are underpinned by structural inequalities and institutional discrimination. In order for Palestinians to receive medical treatment, they must go through an exit-permit system administered by the Israeli government. Structural factors like this create an environment where health disparities can foster but also become more challenging to address. Furthermore, while this system already limits access, occupying forces, economic blockades, and increased attacks on facilities caused by the conflict further hamper the delivery of essential health services and deepen the humanitarian crisis.

- Health Infrastructure. The racialization of resource distribution (or blockage) stemming from the conflict plays a direct role in shaping major public health concerns in the humanitarian crisis, like higher mortality rates, increased rates of malnutrition, and poorer overall health. With an increased lack of access to clean water, adequate nutrition, and basic sanitation, public health outcomes worsen and disproportionately affect children and the elderly, leading to the formation of health disparities among populations. The Israeli blockade of Gaza, for example, has led to shortages of medical supplies and a breakdown in healthcare infrastructure, exacerbating the suffering of those affected.

- Mental Health. The psychological impact of sustained conflict can result in long-term complications. The trauma experienced by Palestinian civilians, including exposure to violence, displacement, and loss of loved ones, leads to significant mental health issues. Studies show high rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety among those living in conflict zones and during the aftermath. Additionally, in the case of Palestinians, the ethnic and racial dimensions of this trauma are important. Being a member of an ethnic group that faces systemic discrimination and violence can intensify feelings of marginalization, hopelessness, and dehumanization. This creates an added layer of stress and trauma tied to their ethnic identity on top of the physical health effects caused by the humanitarian crisis.

The unique discrimination Palestinians face in the conflict zones regarding receiving healthcare and medical treatment fundamentally follow the idea of ‘medical apartheid’. The intersection of race, ethnicity, and humanitarian crises in the context of genocide highlight the complex ways in which identity and conflict influence health outcomes.

These complex dynamics serve as a stark reminder of how deeply rooted discrimination continues to manifest in modern conflicts. By confronting these factors, we can strive toward responses that not only address the immediate needs of affected populations but also work to dismantle the structures of inequality that perpetuate suffering, ensuring that all affected populations receive the support and care they need.

Rahim is a guest blogger at UITAC Publishing. UITAC’s mission is to provide high-quality, affordable, and socially responsible online course materials.

Images used in this blog:

- “Hanging Country’s Flags” by Karan Dalal is licensed on Pexels. This image has not been altered.

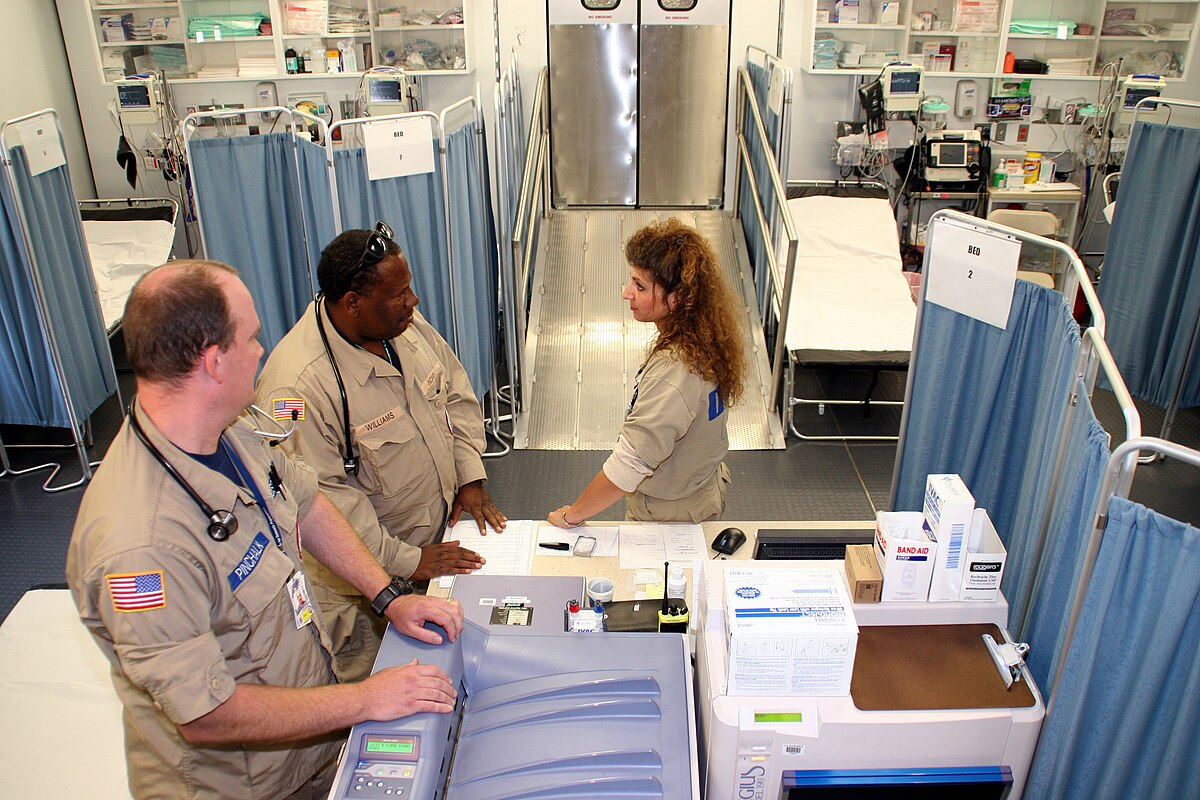

- “Humanitarian aid in Donetsk” by UNICEF Ukraine is licensed under CC BY 2.0. This image has not been altered.