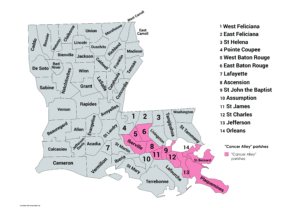

Nestled among the riverbank of the Mississippi River, between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, lies the area colloquially known as Cancer Alley. At 85 miles long, it is not only home to 1.5 million people, but also to around 200 fossil fuel and petrochemical companies. The proximity of these companies and unenforced environmental standards is wreaking havoc on the area’s predominantly African American population, leading to increased risks of cancer and other health hazards. Cancer Alley environmental activist Sharon Lavigne (image) has shared stories of how every single person in her community knows someone suffering from cancer. “It’s a death sentence,” Lavigne has said, referring to the endless exposure to industrial pollution.

Nestled among the riverbank of the Mississippi River, between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, lies the area colloquially known as Cancer Alley. At 85 miles long, it is not only home to 1.5 million people, but also to around 200 fossil fuel and petrochemical companies. The proximity of these companies and unenforced environmental standards is wreaking havoc on the area’s predominantly African American population, leading to increased risks of cancer and other health hazards. Cancer Alley environmental activist Sharon Lavigne (image) has shared stories of how every single person in her community knows someone suffering from cancer. “It’s a death sentence,” Lavigne has said, referring to the endless exposure to industrial pollution.

Cancer Alley’s environment is toxic to its inhabitants. Fossil fuel and petrochemical companies routinely release pollutants into the air, often exceeding the environmental standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). These pollutants include chemicals like ethylene oxide and benzene, known powerful carcinogens, which attack the physical well-being of residents. As a result, this region has had cancer rates up to seven times the national average, with breast cancer, prostate cancer, and liver cancer being common. Other serious health hazards are reproductive and respiratory disorders. Women experience miscarriages, low birth weights, and stillbirths at higher rates than the national average, and typically experience riskier pregnancies with more difficult symptoms. Chronic asthma, severe coughs, and lung problems are common in this area. However, despite these flagrant health issues, new petrochemical companies keep popping up and taking up residence in the area, with little government oversight to protect citizens.

Government authorities have failed the people in Cancer Alley on multiple levels. At the state level, Louisiana’s government has prioritized the interests of the petrochemical industry over the health and safety of its residents. It has allowed petrochemical companies to operate with minimal oversight, releasing toxic compounds into predominantly Black and low-income communities. On the federal level, the EPA has failed to protect human health and the environment. Despite years of increasing evidence and pleas from the community, the EPA has failed to properly enforce the Clean Air Act and other environmental protections. With the defunding of the EPA, firing of environmental staff, and environmental standards growing more lenient, it is likely that environmental issues like these will only grow worse. In response to these systemic failures, residents of Cancer Alley have fought back against the petrochemical companies. They have led marches, protests, and filed lawsuits to prevent new companies from being established. Still, their fight continues, and environmental justice remains an ideal, not a reality.

This phenomenon in Cancer Alley is not an anomaly; it is a textbook example of environmental racism. Environmental racism is the greater likelihood of people of color experiencing environmental problems. It is a persistent issue that plagues marginalized communities, both big and small, today, exposing them to health hazards, creating financial burdens, and establishing a poorer quality of life. It is deeply rooted in broader social structures. Sociological theories like critical race theory and conflict theory help explain how systemic inequality and segregation shape unequal environmental protections. Critical race theory is a framework that describes how systemic racism is part of American society, shaping everything from education to housing and healthcare. Racism is not an individual issue but one embedded in American laws and institutions. Through the lens of critical race theory, one can analyze why poor people of color are affected by environmental disasters and pollution at higher rates. Race plays an important role in understanding the harm committed in Cancer Alley.

Another important sociological lens for analyzing environmental racism is conflict theory. This is a sociological perspective emphasizing the role of political and economic power and oppression as contributing to the existing social order. Communities of color have historically been marginalized and stripped of their political and economic power through unfair wages, discriminatory policies, and a lack of political representation. Even today, Black and Hispanic workers typically earn less than non-Hispanic white workers, even with accounting for the same level of education in the same field. Industrial companies choose to build their hazardous facilities close to the homes of people of color because they have fewer legal protections and fewer resources to fight back. Using the lens of conflict theory demonstrates how capitalism, as seen through the industrial companies, prioritizes economic profit over people.

Thus, environmental racism is a form of structural inequality that exposes marginalized groups to greater environmental risks while shielding wealthier, whiter communities from the same risks. It is both a racial and class issue, seeing as lower-income communities of color have less social power to protest their unjust treatment. In the past, white communities have been able to fight against the placement of polluted companies close to their vicinity. However, when people of color are the victims, the government turns a blind eye.

The consequences of this are ugly. Residents of these communities suffer from disproportionately high rates of diseases. Families watch their children grow up, breathing in toxic air and playing in a home that could ultimately kill them. Some might wonder why these people don’t leave. Economic insecurity is one major factor that stops people from moving away. Not only would one have to leave their job, but living in a polluted land makes it increasingly difficult to sell your property. After all, no one wants to buy a house that will give them cancer. So not only are people in this area suffering health-wise, but they cannot afford to leave.

Another factor that heightens the economic insecurity of an already low-income community is the high price of U.S. healthcare. The price of doctor visits, surgeries, and even medication is exorbitant and leaves many families in debt. For example, asthma inhalers are significantly more expensive in the US compared to other countries. The inhaler QVAR RediHaler costs $286 in the US. In Germany, it costs $9. Same product, same company, but the price has been drastically gouged.

This becomes an even bigger issue when communities are disproportionately affected by diseases and poisoned by their surrounding environment.

Flint, Michigan, a city with a predominantly Black and low-income population of 79,000 people, is another well-known example of environmental racism. Government authorities switched the water supply to the Flint River and failed to properly treat the water. The untreated water corroded old pipes and caused the leaching of lead into the drinking water supply. Although residents complained about the contaminated water, state and municipal government officials ignored the issue for years, until, after increased media awareness and protests, the federal government forced them to begin replacing the lead pipes and ensuring safe drinking water. The years of exposure to lead among residents led to various health effects, such as developmental delays, neurological disorders, and more.

Flint, Michigan, a city with a predominantly Black and low-income population of 79,000 people, is another well-known example of environmental racism. Government authorities switched the water supply to the Flint River and failed to properly treat the water. The untreated water corroded old pipes and caused the leaching of lead into the drinking water supply. Although residents complained about the contaminated water, state and municipal government officials ignored the issue for years, until, after increased media awareness and protests, the federal government forced them to begin replacing the lead pipes and ensuring safe drinking water. The years of exposure to lead among residents led to various health effects, such as developmental delays, neurological disorders, and more.

As seen in the case with Flint, Michigan, there are ways to demand justice and change. Environmental racism is a long-persisting issue, one that has impacted communities for generations, creating long-lasting trauma surrounding what should be someone’s safe place: their home. However, racial and environmental activists are fighting back to protect their land. Grassroots organizing is useful in gathering the community together. Many activists partner with environmental law groups to file lawsuits against polluters and seek federal government intervention. Public awareness is an effective tool as well, with many activists organizing marches and protests to raise awareness of their situation. Recent years have seen surges in marches to raise awareness of environmental racism and its effect on marginalized communities.

In Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, environmental activist Sharon Lavigne has united her parish and the surrounding community to fight against industrial pollution. They’ve marched in protest of substandard government protection, raised awareness of their plight, and have successfully delayed the construction of new petrochemical plants. Lavigne reaffirms the racial aspect of this pollution by discussing how “the civil rights struggle that my parents fought for continues today and we fight for our survival against industrial polluters.”

In Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, environmental activist Sharon Lavigne has united her parish and the surrounding community to fight against industrial pollution. They’ve marched in protest of substandard government protection, raised awareness of their plight, and have successfully delayed the construction of new petrochemical plants. Lavigne reaffirms the racial aspect of this pollution by discussing how “the civil rights struggle that my parents fought for continues today and we fight for our survival against industrial polluters.”

Environmental racism will only become more heightened as climate change makes its mark, devastating communities and ecosystems. However, all is not hopeless. As people raise awareness and join the fight against inequality, policy and public opinion change.

Ramos is a guest blogger at UITAC Publishing. UITAC’s mission is to provide high-quality, affordable, and socially responsible online course materials.

Images Used in This Blog:

- “Cancer Alley Louisiana” by Patapsco913 is licensed by Wikimedia Commons under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

- “Flint Water Tower” by Alberryii is licensed by Wikimedia Commons under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

- “Sharon Levigne 253629” by Frypie is licensed by Wikimedia Commons under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.